Infrasternal Angle: What it is and why its important

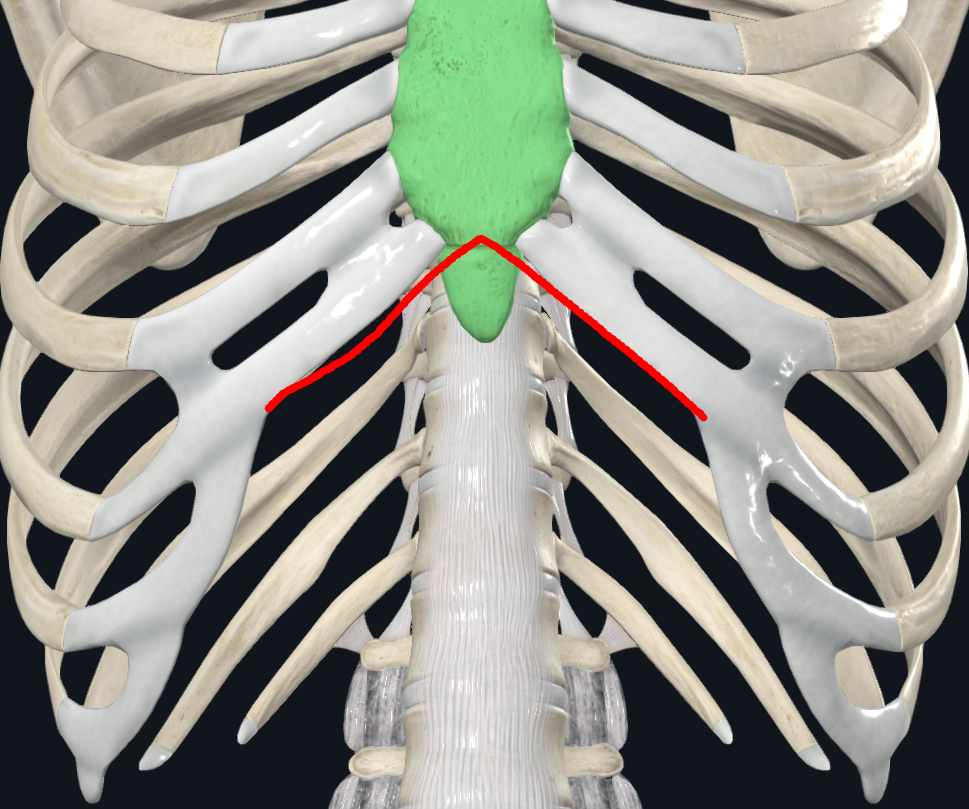

The infrasternal angle (Complete Anatomy app by 3D4Medical from Elsevier)

In the world of human movement, there are so many different variables to consider. Among those variables, I have found one that has become one of the most important things I consider when I am trying to evaluate a client or athlete - the infrasternal angle (ISA).

The ISA is the angle the lower ribs in the ribcage make. This is used as a descriptor of behaviors that somebody is predisposed to. This can also tell you about someone’s breathing excursion because of the way the angle changes (or doesn’t change) as we inhale and exhale. A person that demonstrates an exhaled ribcage would be what’s called a narrow ISA. An exhaled ribcage would be one where the diaphragm rises and brings the ribs back inward, closing the angle. Think about when you breathe out, how the lungs deflate. This will be accompanied by an ascending diaphragm. A narrow ISA creates an angle that is less than 90 degrees. A person that demonstrates an inhaled ribcage would be what’s called a wide ISA. The inhaled ribcage is one where the diaphragm drops to accommodate the increase in size of the lungs as we inhale, thus resulting in a wider angle. A wide ISA has an angle that is greater than 90 degrees. These different ribcage presentations show us the limitations in breathing that each ISA has.

A narrow ISA has an exhaled ribcage, but has a bias toward inhalation. They have an exhaled ribcage because they have an inability to achieve an exhale dynamically, thus demonstrating a limitation in exhalation. The opposite is true for the wide ISA - they have an inhaled ribcage, but have a bias toward exhalation. They have this ribcage shape because of their inability to achieve a dynamic inhalation. Pre-setting this structure, then, is a way to achieve their breathing limitation without having to do it dynamically - the shape is already present, so there eliminates the need to create it dynamically. This can pose a problem - the inability to move the lower ribs (open or close the ISA) is demonstrative of not only limited breathing excursion, but also limited mobility.

Wide ISA on left, narrow ISA on right (Credit: Zac Cupples)

To understand how this limits mobility, we can associate both inhales and exhales with specific joint rotations - inhalation is external rotation (ER) , while exhalation is internal rotation (IR). Any movement away from the midline of the body can be categorized as external rotation. This includes flexion and abduction, as well as external rotation, obviously. Movement towards the midline of the body is categorized as internal rotation. This includes extension and adduction, as well as internal rotation itself. The reason that these positions are classified as rotations is because of how we propel ourselves through space. We do so through rotational movement and not singular straight-plane movement. We do not flex or extend ourselves through space, we externally rotate and internally rotate through space. As we flex and abduct our limbs, there is an actual external rotation of the bone(s) at the same time. It is not just the limbs moving in a straight line. The same is true for when we extend and adduct our limbs - there is internal rotation of the bones occurring there, too. Those movements cannot happen normally if the bone cannot externally rotate or internally rotate. A limitation in the ability to do one or the other can sometimes tell you what somebody’s ISA is, but not always. Both ISAs can also have limitations in the rotation they should be more predisposed to having. For instance, a wide ISA has a bias toward exhalation, which is IR. It is possible for a wide ISA to have limited IR. The same is true of the narrow ISA. They should have ER since they hold an inhalation bias, but sometimes can present with limited ER. The value of knowing the ISA in these situations is that it tells you exactly which measures you need to recapture first, thus narrowing down your exercise selection and making it easier to program for the individual. Certain exercises hold more of an ER bias or IR bias. Squatting, for example, is an ER-biased exercise because it requires that the hip can externally rotate enough to not only start the squat, but also reach the bottom of it. The sacrum must be able to counternutate, which is coupled with hip external rotation. On the contrary, Romanian deadlifts are an IR-biased exercise, because it requires that the hip(s) internally rotate. The hinge position entails nutation of the sacrum, which is coupled with hip internal rotation.

Cusi, M., Saunders, J., Van der Wall, H., & Fogelman, I. (2013). Metabolic disturbances identified by SPECT-CT in patients with a clinical diagnosis of sacroiliac joint incompetence. European Spine Journal, 22, 1674-1682.

Figure 4b, 4c

We can also associate both ER and IR with the concepts of expansion and compression, respectively. Since ER is movement away from midline, it is inherently expansive in nature. We are physically expanding our body and shifting our center of gravity (COG) up. Take a breath in and you will feel you ribcage literally expand and feel yourself rise up. On the other hand, since IR is movement toward midline, it is compressive by nature. We are physically compressing our body, which will lower our COG. When you exhale, you can feel your ribcage shrink in size, and actually feel yourself shrinking (sort of). This is compression of the ribcage.

Taking these concepts into the realm of human movement, the ISAs have their own biases toward different qualities of performance. A wide ISA, with the ability to internally rotate and compress, is a better force producer. This is because internal rotation is force-producing, since compression is force production. We are squeezing our body and muscles to exert force, thus making it compression. Some of the most elite wide ISA athletes in the world are larger individuals, such as powerlifters, offensive lineman in football, and throwers in track and field. On the contrary, a narrow ISA, with the ability to externally rotate and expand, is better at dynamic motion. This is because external rotation is force-absorptive, and expansion occurs when force is being absorbed. With less compression to slow them and a naturally higher COG, they naturally have better movement capability. Since they can expand easily, they can move easily. Some of the most elite narrow ISA athletes in the world are field/court athletes - they tend to participate in sports where you are changing direction often because they generally can do that well. Knowing wide ISAs are good force-producers and narrow ISAs are good force-absorbers, you can tailor your plyometric/power training to bias different qualities and give the athlete or client in front of you exactly what they need to move well. You can also tailor some strength exercises to bias the behaviors you want your client/athlete to train.

To understand how to bias plyometric/power training for different ISAs, we must know how connective tissue behavior differs between the ISAs. Since the wide ISA is biased toward force production and compression, this also means that their connective tissue is biased towards overcoming connective tissue (CT) behavior. They do not yield very well, but since their natural inclination is to produce force, their bias is toward more overcoming CT behavior. On the other hand, the narrow ISA is biased toward force absorption. With this bias, they have a natural inclination toward yielding CT behavior. They can accept force very well because their natural bias is that, which means their CT can more easily yield. They struggle with generating an overcoming action with their CT. With this knowledge of connective tissue behavior, you can manipulate exercises to attain a quality you desire. You can train the wide ISA to absorb force with movements that require them to stick a landing, or absorb an incoming force (think catching or chopping a medicine ball). On the contrary, you can train a narrow ISA to produce more force with movements that require a quick rebounding action, such as repeated jumping or repeat med ball throws.

All of this general insight into the ISA and what it represents is important because it will allow a practitioner to tailor their programming with utmost precision to the person they have in front of them. Instead of applying general strength exercises or standard plyometric exercises, the practitioner can now manipulate the constraints of different exercises to achieve exactly what their client or athlete needs. They are now fine-tuning exercises to get the most they can out of who they train. Within the world of coaches and training, we always talk about every situation being an n=1 type of situation, but most still apply general interventions across a multitude of people without consideration of other factors. This is not n=1. Understanding what the infrasternal angle can tell us gives us the ability to truly apply a specific intervention to a specific person to attain a specific outcome. This knowledge improves the specificity of intervention and will ultimately lead to greater results, better athletes, and improved client health.

This is a list of the biases of each infrasternal angle:

| Wide | Narrow |

|---|---|

| Compression | Expansion |

| IR | ER |

| Force | Motion |

| Exhalation | Inhalation |

| Lower COG | Higher COG |

References

3D4Medical (2023). Complete Anatomy (Version 9.7.4.0) [Desktop App]

Cusi, M., Saunders, J., Van der Wall, H., & Fogelman, I. (2013). Metabolic disturbances identified by SPECT-CT in patients with a clinical diagnosis of sacroiliac joint incompetence. European Spine Journal, 22, 1674-1682, Figure 4b-c.