Front Squat vs. Back Squat: Which to Use and Why

Barbell squats are probably an elite exercise and one of my all time favorites for driving strength. Back squats are the most popular type of squat done, but front squats are finding their spot in the world of sport performance. This raises the question - should I/my clients or athletes back squat or front squat? As always, context will matter when picking an exercise, but being able to understand the context you are working within will assist greatly in guiding your decision making for picking either a back squat or front squat. One’s infrasternal angle will also determine which squat will be better for that body type.

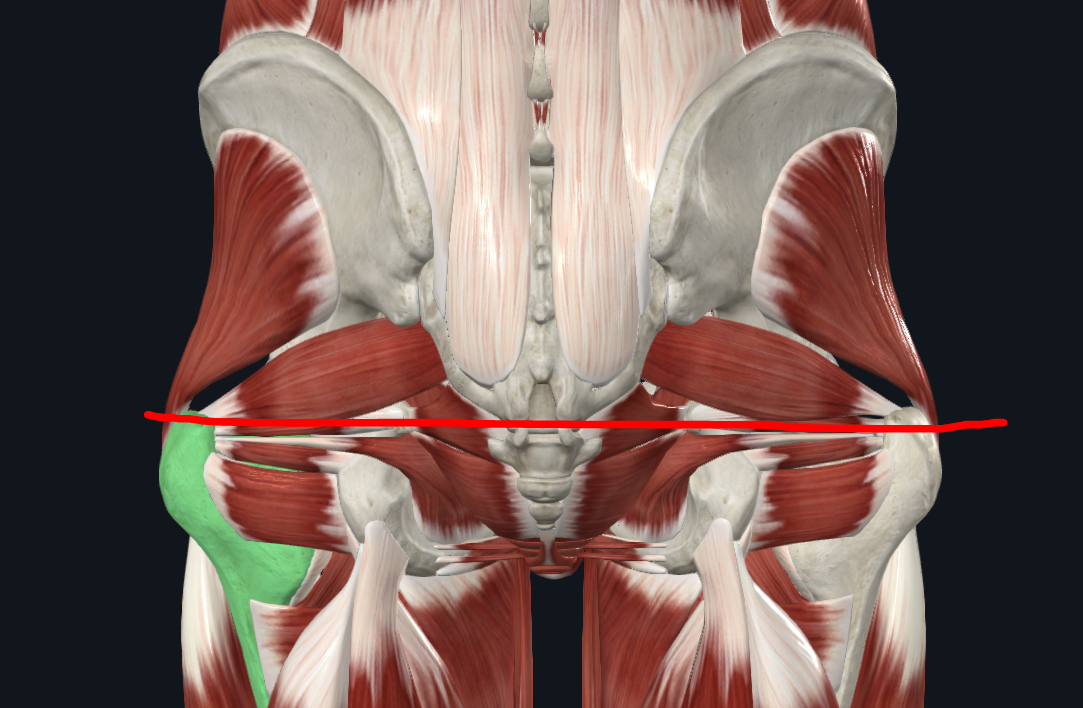

To start understanding why one squat will work better for a specific infrasternal angle, one must understand the delineation of the posterior pelvis musculature and how the different muscles in the posterior pelvis work. You can delineate these muscles by drawing a line across the pelvis from the greater trochanters of each femur. This will split up the pelvis muscles into posterior upper and posterior lower regions. They will behave differently relative to each other. This is due to the movement of the sacrum and innominates (the hip bones). For the sacrum to counternutate, the posterior upper muscles of the pelvis must “lengthen” (eccentrically orient) while the posterior lower muscles of the pelvis will contract (concentrically orient). If the posterior upper muscles do not eccentrically orient, the sacrum will not be able to counternutate because there will be too much compressive force preventing its movement. Now, for the sacrum to nutate, the posterior upper muscles will concentrically orient while the posterior lower muscles eccentrically orient. The posterior lower must eccentrically orient for the apex of the sacrum to move back in space as nutation occurs. If they do not eccentrically orient, there will be no space for nutation to occur.

Greater trochanters are the delineation point (don’t judge my not straight line) - Credit Complete Anatomy by 3D4Medical (above and below)

NOTE: The glute max can also be split up into posterior upper and posterior lower regions.

With this background, we can now start to understand why one squat is better for a specific infrasternal angle than another. The narrow infrasternal angle has a concentric bias in the musculature on the frontside of the body, meaning they will have more expansion naturally in the posterior aspect of the thorax, which is where the spine will naturally move. For the spine to move backwards in space, the scapulae must internally rotate, or “protract,” to reduce the compressive force of the musculature on the backside of the body. As the spine moves backwards, the sacrum must also counternutate. As we established, counternutation is paired with eccentric posterior upper musculature in the pelvis. Therefore, the bias of the narrow infrasternal angle is one of counternutation in the sacrum. The wide infrasternal angle has a concentric bias in the musculature on the backside of the body, meaning they will have more expansion naturally in the anterior aspect of the thorax, which again is where the spine will naturally move. For the spine to move forwards in space, the scapulae will externally rotate, or “retract,” compressing the posterior aspect of the thorax and allowing musculature on the front side of the body to eccentrically orient (think pecs, rectus abdominis). As the spine moves forwards, the sacrum must also nutate. Nutation is paired with eccentric posterior lower musculature in the pelvis. The bias of the wide infrasternal angle is one of nutation in the sacrum.

Counternutation is associated with ER, which is our space for force production, nutation is associated with IR, which is our actual force production. We require ER to IR.

When loading a front squat, the anterior loading will manipulate the center of gravity backwards in space. This opens up the posterior aspect of the thorax, leading to more counternutation of the sacrum relative to a back squat. It would lead to reason that narrow infrasternal angles will be better at front squatting than back squatting (they are better squatters overall but that’s for another day) because their bias is already one of posterior expansion. When loading a back squat, posterior loading will push the center of gravity forward. This means that there will be more nutation of the sacrum. Therefore, wide infrasternal angles will be better at back squatting than front squatting (but they don’t really squat well in general) because their bias is anterior expansion. These different squats play into the natural tendencies of specific infrasternal angles, predisposing them to being better at one variation vs. the other. Personally, I can back squat much better than I front squat because I am a wide ISA.

Front squat shifts my COG back. You can see my structural bias because I cannot counternutate my sacrum; it maintains a nutated position (wide ISA bias).

Back squat shifts my COG forward. I attain this position much better because of my nutation bias. Also compare the ab position here. Shows the shift of COG.

Now context comes into play - what if you have a wide ISA that is a soccer player… should you back squat them because they’re a better back squatter? Maybe.

How about a narrow ISA that is a T&F thrower… should they front squat? Maybe.

The demands of sport come into play, and your training goals also come into play. If you have the wide ISA soccer player and you want to improve their ability to play soccer, you will probably want them to front squat so you do not compress their space and take away movement for the purposes of force production

… BUT…

If your goal is to improve their strength, it could be useful to back squat them so long as they don’t become slower. The demands of sport in this context are paramount and must be considered. This sort of thing also applies to the general population - to improve mobility, front squats are better than back squats because of the overall bias of the movement.

The same considerations can be made for the narrow ISA thrower. They benefit from more force because of what they do, so a back squat naturally would make sense. That said, they still need to retain SOME mobility because of the rotational demands that come with being a thrower. If their throwing distance starts to suffer, you should consider taking a look at how much they are back squatting and consider a front squat to restore some mobility while keeping their force production somewhat high still. Same thing applies here - consider the performance of sport when looking at what to program. It is also good to program different squats for the sake of variety. Doing front squats or back squats all the time can get old quickly.

In the end, context is king, but do not neglect other factors like a person’s structure (infrasternal angle) and therefore their physical capabilities, their sport and performance within the sport, and enjoyment of lifts.